In the beginning, the earliest functional iteration of a large scale network was funded by Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and it created a link between UCLA and Stanford Research Institute in October 1969. By December of the same year, two more universities were added to the network: the University of Utah, and the University of California. At that time, it was known as the ARPANET.

With these networks growing so quickly, a problem eventually became apparent. There was no central global address book.

Computers communicate much the same way as the global Postal systems work. On an envelope, a sender will include both their originating address and the destination address. A computer will do likewise, but first it must know the destination address. And this isn’t just for email — it’s for everything. Every act you perform on the internet is just a series of messages back and forth. And at that time, unlike our friendly-named streets and cities, computers relied on mathematical formulas and strange binary information to form their addresses (they still do, but now also have DNS). So these universities had to manually keep a special text file on each of their computers that listed the IP address and name of every other computer on the network. If someone wanted to add a new system to the network each computer would need to add it manually. So you can see how this would quickly be found burdensome. Imagine if every time a new website opened, we needed to look up the information and then put it in a massive text file. Manually. Billions of times.

At it’s core, what DNS does is match up the un-friendly binary IP address information with more friendly names. So instead of browsing Google by going to http://173.194.123.34 (which works, incidentally, at the time this post was written), you can simply type in “google.com” and then DNS checks who google.com is, and it goes from there. This is why you hear websites and IT people talking about a “Domain Name” — the friendly-name portion of the Domain Name System or, DNS. By the 80’s DNS was pretty mainstream.

Another use for DNS is that it tells incoming communications which server to use to deliver things like Email, which is called a Mail eXchange (MX) record, because most large enterprises have a vast number of servers, each with a specific purpose, so it is not practical to have one address that does everything.

So who controls who gets what Domain Name? That would be the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) who, in turn, delegate authority to other organizations to maintain it. You don’t ever really own a Domain Name, you merely lease it for a period of time. You can keep it for as long as you continue to renew it, or decide to sell it.

The virtue of DNS is the fact that the friendly alias is easy to remember. The simpler the name, the easier it is for people to remember, and theoretically the more visitors one can expect. Because Domain Names are so relatively inexpensive, this has led to Domain Name hoarding, which is why so many new web platforms have odd misspelled names. All the normal dictionary words are already taken, often by people looking to make money on selling them to the highest bidder. The names themselves have a perceived value — the most expensive domain name to date was Insurance.com, purchased for $35.6 Million in 2010.

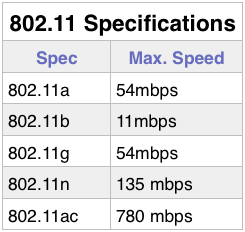

Someone asked me recently how best to set up a wireless router so that streaming and general internet use are both quick.

Someone asked me recently how best to set up a wireless router so that streaming and general internet use are both quick.

An integral part of a secure network is the Firewall. But why? What is it? Does everyone need one?

An integral part of a secure network is the Firewall. But why? What is it? Does everyone need one?